History of the cathedral

Nine centuries of history

The history of the Cathedral should be viewed in the light of important social and cultural shifts that saw Otranto, an important Byzantine provincial capital between the 6th and 11th centuries, reduced to a frontier territory and “Latinised” with the arrival of the Normans in the 11th century.

Everything inherited from the Byzantine Empire (language, liturgy, spirituality, schools and other institutions) went through profound changes that signalled a shift away from one civilisation and the birth of a new one over time.

It was within this backdrop that we find the decision of the then Archbishop of Otranto to build a new church in the city, the Cathedral, dedicated to the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

This new church would be a tangible sign and symbol in which Normans and Byzantines, victors and the vanquished, would be able to find themselves and recognise one another as brothers in faith.

The stages of the Cathedral

The new church was built on Colle Idro, a hill that was the site of a Roman domus which probably also served as a place of worship. Its construction was made possible by the financial support of Roger, Duke of Apulia and Calabria, and from voluntary donations and services from the people of Otranto, who were encouraged to help with the construction through the transport of stones, mortar, timber and anything else required for this ambitious enterprise.

The building, which takes the form of a basilica in the shape of a Latin cross, was completed in just eight years and was consecrated in 1088 in the presence of archbishops from across the Terra d‘Otranto, Duke Roger and the Pontifical Delegate, the Archbishop of Benevento, the capital of the region’s Norman rulers.

Several years later, Bishop Jonathas commissioned Presbyter Pantaleone to carry out an extraordinary work that would have to cover the floor of the new church: the mosaic.

The cathedral was very different in Pantaleone’s day compared to what it is now, and throughout its history it has undergone and overcome major tests, including the ravages of time and those of humans themselves.

We can only try to imagine how different the cathedral looked during Pantaleone’s time, covered in frescoes that were destroyed by the Ottomans in 1480 who, after laying siege to and capturing the city, transformed the building into a mosque, leading to the destruction of not only the internal artwork but also the external façades.

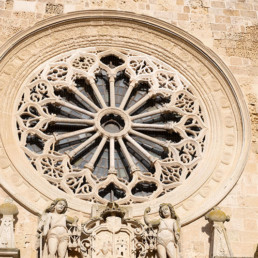

Towards the end of the 15th century Archbishop Serafino da Squillace rebuilt the outer walls that had been torn down during the siege and added the Renaissance rose window with its 16 highly decorated panels.

In 1673 Archbishop of Otranto Adarzo de Santander commissioned the high-embellished baroque doorway for the Cathedral’s façade, with columns mounted with pinnacles in the shape of pinecones.

Towards the end of the 17th century Mgr. Francesco Maria De Aste extensively transformed the nave by decorating it with stuccos and frescoes.

During his tenure as Bishop, De Aste demolished the side apses and bult the chapels dedicated to the Otranto Martyrs and the Blessed Sacrament, as well as removing the iconostasis (as stated in the visiting records of Mgr. Lucio De Morra), the dividing structure used by churches at the time to separate the parts of the church reserved for the clergy and that of the lay people.

Among the works and additions carried out, the original painted wooden trusses that supported the Romanesque double-pitched roof, visible from the outside of the cathedral, were concealed and an exquisite wooden false ceiling with octagonal coffers, in a Moorish-Islamic style and painted and decorated with pure gold, was built to replace it.

In the 18th century, Mgr. Michele Orsi commissioned a series of new works on the cathedral’s interior, including the false ceilings in the transept, the construction of an imposing marble altar (removed in the mid-20th century) and the ornamentation of the stuccos on the cathedral’s façade (removed in 1912).

The wooden false ceilings in the aisles commissioned by Mgr. Andrea Mansi date back to 1827 and have designs which recall the beautiful tapestries that would have once adorned the cathedral’s walls.

At the end of the 20th century, Archbishop Vincenzo Franco arranged for the restoration of the floor mosaic, under the bedding mortar of which were found ancient mosaics dating back to the early Christian period and 42 burials (Messapian, Roman, Byzantine and Medieval).

Extensively redesigned and restored over the course of nine centuries, the Cathedral continues to inspire awe and wonder thanks to its floor mosaic, the declaration of faith by the Otranto Martyrs and, to this day it continues to teach us how the dialogue between East and West, and between Jews, Christians and Muslims, can guide homo viator.

The martyrs’ chapel

Within the cathedral itself there is another important point of interest next to the mosaic with which it has an important link: the Relics of the 813 inhabitants of Otranto who, through declaring their faith in Christ, were massacred in 1480 by Ottoman Turks who had sailed from the Levant, a region with which the city of Otranto had fostered ties and relations for centuries.

From a Christian perspective, the events of 1480 were the results of the centuries-old history of and education in faith of a people for whom the mosaic acted as their main source of religious “schooling”. Most likely we would not have had one without the other, as it was the very act of walking over the tiles of the mosaic and following the path laid out by the Tree of Life (a symbol of Christ) that the people of Otranto learned about something worth living (and, if necessary, dying) for.

On 28th July 1480 a large fleet under the command of Gidek Ahmet Pasha was spotted sailing through the Strait of Otranto. The Ottomans, who had seized Constantinople in 1453 and declared the end of the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire, landed on the most easterly point of the Salento Peninsula and besieged and seized the city of Otranto in just 15 days.

Woman and children were enslaved, thousands of inhabitants were killed, and 813 men were asked to renounce their faith in order for their lives to be spared.

It was 14 August 1480, a memorable date for Otranto.

The people of Otranto faced Ottoman execution: the first to be beheaded was a humble cloth shearer, Antonio Pezzulla, later renamed 'Primaldo' because he was the first to pay for his faith in Christ with his life. He urged the people of Otranto not to give in and to choose to die for Christ, who had died on the cross for them.

Chronicles of the time recount that the body of Primaldo himself remained standing until the end of the execution. At the sight of these events, the executioner Berlabei converted to Christianity and, as an apostate, was then condemned to the terrible penalty of impalement.

The city was liberated after about a year by the Aragonese army. Duke Alfonso of Aragon arranged to collect the bodies of the Ottocento, which had remained intact on Minerva Hill for a year. The Ottocento were transferred, together with the beheading stone, to the Idruntine Basilica and, in part, to Naples, then capital of the Aragonese kingdom.

The Otranto event immediately entered popular piety and the collective imagination.

Antonio Primaldo and Compagni were beatified in 1771 and canonised in St. Peter's Square by Pope Francis on 12 May 2013.